Vaidehi’s ‘Akku’: The ‘Mad Woman’ As Reaction To Trauma In A Patriarchy

Dr Vaidehi’s classic story Akku examines the ‘mad woman’ as a product of trauma inflicted by an unequal, patriarchal society, adapted to screen as Ammachi Yemba Nenapu.

October 10th is observed as World Mental Health Day by World Health Organization and several other international agencies. October is also Mental Health Awareness Month.

Kendriya Sahitya Akademi awardee Dr Vaidehi’s classic Kannada short story, ‘Akku’ is worth remembering around October 10th, for its exploration of mental health issues as products of social inequalities and injustices.

Adapted into film, plays, and also in textbooks

‘Akku’ has certainly not been forgotten, and has been incorporated into textbooks, films (Ammachi Yemba Nenapu streaming on Amazon Prime currently) and plays recently.

Mental health issues a combination of social factors and brain chemistry

Nevertheless, its importance lies in reminding us of one timeless truth: mental health issues do not occur outside of society; they cannot be separated from situations and social situations.

Scientific studies that view depression as the result of chemical process in the brain alone, steer attention away from societal inequalities that trigger depression. Whereas, women’s mental health issues suggest that this might be putting the cart before the horse. After all, our brains are responding to the worlds they encounter.

A synthesis of both positions is now widely recognized: mental ill-health is a result of both societal and biological factors.

Akku’s understanding of patriarchy

In Akku, we meet with an unstable woman, whose instability originates in her misfortunes created and sustained by society. Early on, we are told that Akku’s dumbness was not there from the very beginning.

Even as we see Akku’s own sharp tongue, meaningless pursuits, and others’ mockery of her, Akku’s intelligence shines forth.

Akku’s seemingly mindless questioning of the narrator’s dressing up for her wedding reveals her deep understanding of patriarchy and its normalization in the institution of marriage. We see that Akku may not have coped well with the injustices her marriage dealt her, but her comprehension of the issues at hand are in no way flawed. If anything, they are more accurate than the romanticized understanding of marriage other young women in the family have.

The so-called unstable Akku clearly reasons, even as she pulls out flowers from the hair of the bride-to-be: “Enough of this beautification! If he marries you because of your beauty, for certain, he will not stay by you, write that on the wall!”

Muddling the line between sanity and insanity

Retaliating against those who snigger at her, Akku inadvertently reveals a hidden affair, another sharp truth that shows that neither her moral world nor her power of observation is flawed.

As the story progresses, we meet other women who have suffered due to wayward men and Akku herself has fought off a neighbor who has attempted to assault her. We are then told that Akku’s husband had followed a sanyasi/renunciant deserting her. Akku’s make-believe pregnancies reveal a series of unfulfilled desires that turn up as traumas.

The word psycho-somatic gains a world of meanings in the story. For all her insanity, Akku promptly rejects her husband when he returns, showing strength and courage that elude many women in bad marriages.‘Akku’ muddies the lines between sanity and insanity, showing how social inequalities can have tragic consequences for the powerless. It leaves us wondering why women are thought of as mad even when they speak the truth or, especially when speak the truth.

‘Akku’ is a story that men and women of upcoming generations must read and carry forward as a part of our collective literary and feminist inheritance.

This article uses C Vimala Rao’s translation of the Kannada story.

Sushumna Kannan is the author of Hinduism and Violence, forthcoming, 2021.

Dr Vaidehi’s classic story Akku examines the ‘mad woman’ as a product of trauma inflicted by an unequal, patriarchal society, adapted to screen as Ammachi Yemba Nenapu.

October 10th is observed as World Mental Health Day by World Health Organization and several other international agencies. October is also Mental Health Awareness Month.

Kendriya Sahitya Akademi awardee Dr Vaidehi’s classic Kannada short story, ‘Akku’ is worth remembering around October 10th, for its exploration of mental health issues as products of social inequalities and injustices.

Adapted into film, plays, and also in textbooks

‘Akku’ has certainly not been forgotten, and has been incorporated into textbooks, films (Ammachi Yemba Nenapu streaming on Amazon Prime currently) and plays recently.

Mental health issues a combination of social factors and brain chemistry

Nevertheless, its importance lies in reminding us of one timeless truth: mental health issues do not occur outside of society; they cannot be separated from situations and social situations.

Scientific studies that view depression as the result of chemical process in the brain alone, steer attention away from societal inequalities that trigger depression. Whereas, women’s mental health issues suggest that this might be putting the cart before the horse. After all, our brains are responding to the worlds they encounter.

A synthesis of both positions is now widely recognized: mental ill-health is a result of both societal and biological factors.

Akku’s understanding of patriarchy

In Akku, we meet with an unstable woman, whose instability originates in her misfortunes created and sustained by society. Early on, we are told that Akku’s dumbness was not there from the very beginning.

Even as we see Akku’s own sharp tongue, meaningless pursuits, and others’ mockery of her, Akku’s intelligence shines forth.

Akku’s seemingly mindless questioning of the narrator’s dressing up for her wedding reveals her deep understanding of patriarchy and its normalization in the institution of marriage. We see that Akku may not have coped well with the injustices her marriage dealt her, but her comprehension of the issues at hand are in no way flawed. If anything, they are more accurate than the romanticized understanding of marriage other young women in the family have.

The so-called unstable Akku clearly reasons, even as she pulls out flowers from the hair of the bride-to-be: “Enough of this beautification! If he marries you because of your beauty, for certain, he will not stay by you, write that on the wall!”

Muddling the line between sanity and insanity

Retaliating against those who snigger at her, Akku inadvertently reveals a hidden affair, another sharp truth that shows that neither her moral world nor her power of observation is flawed.

As the story progresses, we meet other women who have suffered due to wayward men and Akku herself has fought off a neighbor who has attempted to assault her. We are then told that Akku’s husband had followed a sanyasi/renunciant deserting her. Akku’s make-believe pregnancies reveal a series of unfulfilled desires that turn up as traumas.

The word psycho-somatic gains a world of meanings in the story. For all her insanity, Akku promptly rejects her husband when he returns, showing strength and courage that elude many women in bad marriages.‘Akku’ muddies the lines between sanity and insanity, showing how social inequalities can have tragic consequences for the powerless. It leaves us wondering why women are thought of as mad even when they speak the truth or, especially when speak the truth.

‘Akku’ is a story that men and women of upcoming generations must read and carry forward as a part of our collective literary and feminist inheritance.

This article uses C Vimala Rao’s translation of the Kannada story.

Sushumna Kannan is the author of Hinduism and Violence, forthcoming, 2021.

Divorce On H4 Visa Can Go Horribly Wrong For Women: Here’s What You Might Encounter

Divorce on H4 visa can go completely downhill for dependent women who are unfamiliar with their new country.

In 2017, my article Wives On H4 Visa – How Do You Deal With The Depression That Dependency Causes? was published here. A Seattle based lawyer read it and contacted me to become an expert witness to testify in the divorce case of her Indian origin client.

I bring you this case study to illustrate the problems and perils of life not only on the H4 visa but also the EAD. As it turns out, the EAD solves some problems, but not for all. Not equally.

Nina’s story about divorce on H4 visaFrom Nina’s family’s point of view her life was ‘settled.’ She had been married and sent off to Seattle, America, and the couple had a baby. But then, all that glitters is not gold. Nina had been diagnosed with depression and was on medication. The details of her case made it evident that there was so much unexplored in relation to what was happening to those on the H4 visa, some of whom were now receiving the EAD (Employment Authorization Document).

Nina’s negotiating power within the marriage had not increased with an EAD, and it would not until she got a job, brought in money, and healed from her depression. With a degree from India, her chances for employment were low and therefore she was headed for a divorce.

In Nina’s case, the power balance tipped in favour of the husband as the person earning, but they had had a child recently and were now on the path of a custody battle as well.

Nina’s attorney contacted me after reading my article on wives on the H4 Visa. This had primarily focused on how the power balance in a couple with a wife on the H4 visa made her completely dependent on her husband, crippling her self-esteem and sending her into a deep depression.

Nina’s attorney wanted to ask me more about the depression connected with being on an H4 visa. When I decided to testify, we did not know, of course, that Nina would lose custody of her four-year old child. An unthinkable turn of events for numerous Indian women.

A controlling, insensitive husbandThere were several problems with Nina’s marriage, but few can be articulated if one did not access the language of feminism and equality within marriage. The language Nina used (in her quiet confident voice that sounded on my phone), instead, was simply that it was a breach of trust. Of the several things her husband had done, these pained her the most:

(1) curtailing her financial freedom to the point that every expense had to be justified

(2) fixing cameras all over the house on the pretext of watching their child but monitoring all her activities

(3) Tracking and recording her Facebook activity to accuse her later of this and that

(4) Accusing her of watching too much TV and being a slacker.

Simply put, he had been too controlling.

To my mind, watching too much TV and disinterest in learning car-driving are classic symptoms of the H4 visa situation. With no outside life, no job, few friends, and neighbors who do not necessarily socialize, TV and internet are the only things a spouse on the H4 can do! This cannot be an accusation when one is caring for the child all by oneself.

Attached to a child that needs constant attention, sleepless, and with zero adult time, TV is often the only me-time for young mothers.

Sunetra, another new mom there also on an H4 visa, says that in the first year of caring for her velcro-baby, she survived only because she got a TV installed in the bedroom and watched movies with muted settings, subtitles on. No wonder, then, that in the famous Australian dramedy on early motherhood, The Let Down, the protagonist makes a strong argument for escaping into quality Danish drama and efficient broadband! When there is no job, there is no motivation to learn car-driving.

The problems in Nina’s marriageNina’s husband had raised two other objections. She could not feed their child pasta, only Indian food. And, she had to put the baby to sleep in another room. Both these seem trivial.

The first one is unacceptable because kids imitate other kids. If you live in the US, your kid is bound to like a few things you never had in your childhood. Plus, sometimes any food is better than no food. Secondly, hundreds of Indian immigrant parents in the USA retain ways of child-rearing that they subconsciously learnt from their parents. In fact, it is suspected many American parents too co-sleep with their children but do not admit to doing it. But differences in parenting styles makes a justified case for divorce in the west—it is likely that Nina’s husband used it as a tactic to procure divorce.

Nina did not want a divorce; she did not want to break the marriage. But she was hurt by her husband’s breach of trust and was angry at his inability to understand her position.

The difficulties faced by Nina in a job searchSometimes, young mothers need time off from jobs and job search. But husbands can think that their wives are unable to procure a job on the EAD because they are incapable of doing so. The truth is that only half the number of those with EAD have been able to secure jobs, a fact that has emerged on many H4 visa discussion forums.

Those in non-STEM professions have had little success, according to one case in a study released by SAAPRI. Nina had a masters in HR, neither entirely IT-based nor outside of it.

Since Indians are not absorbed into non-IT industries regularly, employers have a distrust of Indian educational degrees. Also, USA has a different way of doing things, which requires obtaining a degree in the country to procure a job. And job placements are so tied to college degrees that it is often impossible to procure jobs outside of the college placement cell.

But husbands who force their wives to work can rarely comprehend the gravity of this because they never face these obstacles themselves. Nina’s husband, at one point of time, wanted her to work as a solution for her depression. Just any work, he insisted. She ended up as a janitor in a restaurant that initially promised her a server’s position. She did not want to work in these positions having obtained a master’s degree—they felt demeaning.

Legal issues faced in divorce on H4 visa: US lawyers have no idea of Indian cultural practices

Lawyers and the court system in the USA do not know much about situations faced by immigrant families. They cannot understand or be responsive to Indian cultural practices and its nuances, although in theory, they must consult the law books of India and USA when judging cases involving Indian Americans.

US or Indian govts not sensitive to needs of wives facing divorce on H4 visa

The classic case of Neerja Saraph Vs. Jayant Saraph 1994 shows just this: divorce on H4 visa was granted through ex-parte because the wife could not appear at court.

In many cases, wives on H4 with no income had no funds to book tickets to travel back and forth to the USA to attend court proceedings—the Indian government does not recognize such divorces anymore to help such women.

US legal system clueless about Indian women’s reality on H4 visa

When I was testifying on Zoom (thanks to COVID-19), I mentioned how getting degrees from the US was a point of contention in immigrant marriages because US education is expensive. Who pays for it, the wives’ parents or the husband was often an uneasy question.

Nina’s husband’s lawyer was taken aback and began questioning me if I knew this family personally—an expert witness must not know the family personally or the full details of the case. Little did he know that this question bugged almost all immigrant families with a spouse on H4 visa.

Women facing divorce on H4 visa unaware of legalities

Women who know the complexities of filing for divorce on H4 visa do what an acquaintance did. Jayashree took her child and flew to India on the pretext of a vacation and filed for a divorce from India. Indian courts are biased towards granting child custody to the mother, which worked in her favour. Unfortunately, Nina was caught unaware.

Nina needed a lawyer who could argue that co-sleeping with children was common in India—but she had an American lawyer. Her American lawyer, however, made several efforts to get experts who could make the culture argument, but there was no guarantee that it would be understood by the American court system.

My advice to Nina was that she consult South Asian Women’s organizations in her city to accentuate the culture argument, but Nina was distrusting of everybody, including her lawyer! She only trusted her parents, but knowing nothing of American culture, they were of no help in fighting the case. Distrust of everybody is another classic symptom of the H4 situation—the person has no acculturation and is unable to determine if she is being helped or hurt.

How things went downhill: The husband tried to take advantage of Nina’s legal situation

When things went bad in the marriage, Nina and her husband started seeing a marriage counsellor. Unfortunately, the counsellor sided with the husband, did not reveal his plans of divorcing Nina, as she is required to, and acted with bias when she repeatedly advised Nina to visit India.

Nina refused to do so since her child was still young. Nina’s husband had not procured an Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) card or passport for the child to enable an India visit. His plan was that when Nina goes to India, he files for a divorce in the USA and that would make it very hard for Nina to come back, to fight the divorce case and the custody battle.

Nina’s refusal to go to India compelled her husband to file for divorce when she was in the USA. He had to move out and pay her maintenance.

US laws about child care worked against Nina

But during the divorce proceedings, a court-appointed official evaluated Nina and declared her an unfit mother.

Nina’s defense was that this evaluation was erroneous; she was a fit mother because the child had never suffered from even minor illnesses under her care; she could not have been doing more.

The questionnaire that this official brought in had yes-no questions. What America is aiming to eliminate through such questionnaires is the human error aspect in its child protective services system that fail children from parental abuse, as in the case of Gypsee Blanchard.

A lack of awareness of Indian culture

We could even argue that the questionnaire was culturally biased. Indian parents co-sleep with their children at the cost of the mother’s sleep. The level of sacrifice that Indian parents make throughout their child’s lives is unknown in American culture.

In sharp contrast, American children move out or live separately when they grow up—adulthood has initiation rites and is complete when one’s offspring is well-adjusted—procures job, marries etc. In India, on the other hand, children may never move out and are cared for by parents at different stages of life in different ways.

So, where India leans one way in parenting style, America leans to the other according to its own cultural norms. Each has advantages and disadvantages; neither is perfect.

The question of custody

Unfortunately, however, in Nina’s case, the questionnaire worked against her, especially when, as she told me “the judge was not listening carefully during trial.” Not surprising, as the judges fall back on the filed documents to speak to them.

Nina’s lawyers might have disproved she was depressed but there remained the matter of child custody. That is, Nina’s depression, whether from unemployment or from post-partum, were both extraneous and would rectify when her situation changed. So, how do US courts decide child custody?

The difficult alternative Nina was givenMy advice to Nina to secure more time with her child was that she must take up the two-year offer her husband had made.

Her husband’s offer was that he would seek a separation and not divorce her for two years, so that she could continue to stay on her spouse visa in the US. His condition, however, was that she had to obtain a degree and a job in that time and secure her future in the USA. After this, he would divorce her, she would be on an H1B visa and they would share the custody of their child.

But Nina was skeptical this would work given the uncertainties that H1B workers suffer from and her own experience with unemployment in the USA.

I felt that Nina was too protected by her parents to be living alone in the US with no familial support. Not all women are made the same, and if the men in our lives cannot understand this, what other meaning is there to a marriage?

Divorce on H4 visa hard on dependent Indian womenIn a time when American women are finding divorcing during COVID-19 very hard, a woman on H4 visa is twice as likely to feel nervous.

Nina’s question was, “Why can’t he come to India where both parents can work and have equal custody? Why do I need to re-educate myself?” But because the child is an American citizen, the court system was likely biased towards protecting an American citizen.

“Why is everyone asking me to adjust although he is such a bad person?” Nina’s exasperation resonates with so many women. Obviously, Nina’s husband did not want to head back to India. Why would he? Not when everything was working well for him! Since Nina and her husband could not come to a consensus, the divorce case became contested and went into trial.

What worked against Nina was also likely the Hague convention that India has not signed. What this means is that if one parent abducts their child across international borders, the child can be returned, and the parent prosecuted. If only the husband had allowed for an OCI card!

Nina could have taken the advice of the Ministry of External Affairs Booklet’s advice to go for an uncontested divorce. But she was too angry and upset for that. When I asked her if she would be alright if the judgment rules her child to stay in the US, she just said that she knew something good was going to happen. She just felt it strongly and that she would take a chance with the judge. This despite her own lawyer’s frustrated declaration that if she won, “it would be a miracle!”

My own advice to Nina was to consider the cultural context. For instance, if the case had been filed in India, her Indian lawyers would have advised her to file a 498A to get justice. Similarly, Nina had to do something about child custody that was US culture sensitive. She had to offer a win-win solution, so the courts perceived her as prioritizing her child’s well-being. Child welfare is of paramount importance at US courts. But Nina was adamant, she left it to chance. That is a mistake in the USA, where everything is planned, reasoned out and anticipated well-in-advance. Nina had to think through the worst-case scenario and move forward. Instead, she was optimistic and hopeful.

Judgement ruled against NinaWhen the judgment ruled that the child stay with the father, Nina perceived it as harsh. Nina’s husband is ordered to buy her tickets for her 2-3 visits per year until the child turns six. At 12, the child can choose a parent. Being on an H4 visa, Nina must now return to India as soon as the divorce formalities are through.

The tragedy of this case is that what caused Nina’s depression in the first place, is also the cause for her loss of child custody and her divorce—the H4 visa. Clearly, nobody showed Nina’s husband this article published on Women’s Web. Husbands do not necessarily understand what unemployment in a cold, rainy city and caring for a child 24/7 can feel like—that of course, is patriarchy for you.

Dr. Sushumna Kannan owns Writing in Gold, a Writing-Editing service business based in San Diego, USA. She is the author of Hinduism and Violence, forthcoming, 2021. Check out her other writings at sushumnakannan.weebly.com

Divorce on H4 visa can go completely downhill for dependent women who are unfamiliar with their new country.

In 2017, my article Wives On H4 Visa – How Do You Deal With The Depression That Dependency Causes? was published here. A Seattle based lawyer read it and contacted me to become an expert witness to testify in the divorce case of her Indian origin client.

I bring you this case study to illustrate the problems and perils of life not only on the H4 visa but also the EAD. As it turns out, the EAD solves some problems, but not for all. Not equally.

Nina’s story about divorce on H4 visaFrom Nina’s family’s point of view her life was ‘settled.’ She had been married and sent off to Seattle, America, and the couple had a baby. But then, all that glitters is not gold. Nina had been diagnosed with depression and was on medication. The details of her case made it evident that there was so much unexplored in relation to what was happening to those on the H4 visa, some of whom were now receiving the EAD (Employment Authorization Document).

Nina’s negotiating power within the marriage had not increased with an EAD, and it would not until she got a job, brought in money, and healed from her depression. With a degree from India, her chances for employment were low and therefore she was headed for a divorce.

In Nina’s case, the power balance tipped in favour of the husband as the person earning, but they had had a child recently and were now on the path of a custody battle as well.

Nina’s attorney contacted me after reading my article on wives on the H4 Visa. This had primarily focused on how the power balance in a couple with a wife on the H4 visa made her completely dependent on her husband, crippling her self-esteem and sending her into a deep depression.

Nina’s attorney wanted to ask me more about the depression connected with being on an H4 visa. When I decided to testify, we did not know, of course, that Nina would lose custody of her four-year old child. An unthinkable turn of events for numerous Indian women.

A controlling, insensitive husbandThere were several problems with Nina’s marriage, but few can be articulated if one did not access the language of feminism and equality within marriage. The language Nina used (in her quiet confident voice that sounded on my phone), instead, was simply that it was a breach of trust. Of the several things her husband had done, these pained her the most:

(1) curtailing her financial freedom to the point that every expense had to be justified

(2) fixing cameras all over the house on the pretext of watching their child but monitoring all her activities

(3) Tracking and recording her Facebook activity to accuse her later of this and that

(4) Accusing her of watching too much TV and being a slacker.

Simply put, he had been too controlling.

To my mind, watching too much TV and disinterest in learning car-driving are classic symptoms of the H4 visa situation. With no outside life, no job, few friends, and neighbors who do not necessarily socialize, TV and internet are the only things a spouse on the H4 can do! This cannot be an accusation when one is caring for the child all by oneself.

Attached to a child that needs constant attention, sleepless, and with zero adult time, TV is often the only me-time for young mothers.

Sunetra, another new mom there also on an H4 visa, says that in the first year of caring for her velcro-baby, she survived only because she got a TV installed in the bedroom and watched movies with muted settings, subtitles on. No wonder, then, that in the famous Australian dramedy on early motherhood, The Let Down, the protagonist makes a strong argument for escaping into quality Danish drama and efficient broadband! When there is no job, there is no motivation to learn car-driving.

The problems in Nina’s marriageNina’s husband had raised two other objections. She could not feed their child pasta, only Indian food. And, she had to put the baby to sleep in another room. Both these seem trivial.

The first one is unacceptable because kids imitate other kids. If you live in the US, your kid is bound to like a few things you never had in your childhood. Plus, sometimes any food is better than no food. Secondly, hundreds of Indian immigrant parents in the USA retain ways of child-rearing that they subconsciously learnt from their parents. In fact, it is suspected many American parents too co-sleep with their children but do not admit to doing it. But differences in parenting styles makes a justified case for divorce in the west—it is likely that Nina’s husband used it as a tactic to procure divorce.

Nina did not want a divorce; she did not want to break the marriage. But she was hurt by her husband’s breach of trust and was angry at his inability to understand her position.

The difficulties faced by Nina in a job searchSometimes, young mothers need time off from jobs and job search. But husbands can think that their wives are unable to procure a job on the EAD because they are incapable of doing so. The truth is that only half the number of those with EAD have been able to secure jobs, a fact that has emerged on many H4 visa discussion forums.

Those in non-STEM professions have had little success, according to one case in a study released by SAAPRI. Nina had a masters in HR, neither entirely IT-based nor outside of it.

Since Indians are not absorbed into non-IT industries regularly, employers have a distrust of Indian educational degrees. Also, USA has a different way of doing things, which requires obtaining a degree in the country to procure a job. And job placements are so tied to college degrees that it is often impossible to procure jobs outside of the college placement cell.

But husbands who force their wives to work can rarely comprehend the gravity of this because they never face these obstacles themselves. Nina’s husband, at one point of time, wanted her to work as a solution for her depression. Just any work, he insisted. She ended up as a janitor in a restaurant that initially promised her a server’s position. She did not want to work in these positions having obtained a master’s degree—they felt demeaning.

Legal issues faced in divorce on H4 visa: US lawyers have no idea of Indian cultural practices

Lawyers and the court system in the USA do not know much about situations faced by immigrant families. They cannot understand or be responsive to Indian cultural practices and its nuances, although in theory, they must consult the law books of India and USA when judging cases involving Indian Americans.

US or Indian govts not sensitive to needs of wives facing divorce on H4 visa

The classic case of Neerja Saraph Vs. Jayant Saraph 1994 shows just this: divorce on H4 visa was granted through ex-parte because the wife could not appear at court.

In many cases, wives on H4 with no income had no funds to book tickets to travel back and forth to the USA to attend court proceedings—the Indian government does not recognize such divorces anymore to help such women.

US legal system clueless about Indian women’s reality on H4 visa

When I was testifying on Zoom (thanks to COVID-19), I mentioned how getting degrees from the US was a point of contention in immigrant marriages because US education is expensive. Who pays for it, the wives’ parents or the husband was often an uneasy question.

Nina’s husband’s lawyer was taken aback and began questioning me if I knew this family personally—an expert witness must not know the family personally or the full details of the case. Little did he know that this question bugged almost all immigrant families with a spouse on H4 visa.

Women facing divorce on H4 visa unaware of legalities

Women who know the complexities of filing for divorce on H4 visa do what an acquaintance did. Jayashree took her child and flew to India on the pretext of a vacation and filed for a divorce from India. Indian courts are biased towards granting child custody to the mother, which worked in her favour. Unfortunately, Nina was caught unaware.

Nina needed a lawyer who could argue that co-sleeping with children was common in India—but she had an American lawyer. Her American lawyer, however, made several efforts to get experts who could make the culture argument, but there was no guarantee that it would be understood by the American court system.

My advice to Nina was that she consult South Asian Women’s organizations in her city to accentuate the culture argument, but Nina was distrusting of everybody, including her lawyer! She only trusted her parents, but knowing nothing of American culture, they were of no help in fighting the case. Distrust of everybody is another classic symptom of the H4 situation—the person has no acculturation and is unable to determine if she is being helped or hurt.

How things went downhill: The husband tried to take advantage of Nina’s legal situation

When things went bad in the marriage, Nina and her husband started seeing a marriage counsellor. Unfortunately, the counsellor sided with the husband, did not reveal his plans of divorcing Nina, as she is required to, and acted with bias when she repeatedly advised Nina to visit India.

Nina refused to do so since her child was still young. Nina’s husband had not procured an Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) card or passport for the child to enable an India visit. His plan was that when Nina goes to India, he files for a divorce in the USA and that would make it very hard for Nina to come back, to fight the divorce case and the custody battle.

Nina’s refusal to go to India compelled her husband to file for divorce when she was in the USA. He had to move out and pay her maintenance.

US laws about child care worked against Nina

But during the divorce proceedings, a court-appointed official evaluated Nina and declared her an unfit mother.

Nina’s defense was that this evaluation was erroneous; she was a fit mother because the child had never suffered from even minor illnesses under her care; she could not have been doing more.

The questionnaire that this official brought in had yes-no questions. What America is aiming to eliminate through such questionnaires is the human error aspect in its child protective services system that fail children from parental abuse, as in the case of Gypsee Blanchard.

A lack of awareness of Indian culture

We could even argue that the questionnaire was culturally biased. Indian parents co-sleep with their children at the cost of the mother’s sleep. The level of sacrifice that Indian parents make throughout their child’s lives is unknown in American culture.

In sharp contrast, American children move out or live separately when they grow up—adulthood has initiation rites and is complete when one’s offspring is well-adjusted—procures job, marries etc. In India, on the other hand, children may never move out and are cared for by parents at different stages of life in different ways.

So, where India leans one way in parenting style, America leans to the other according to its own cultural norms. Each has advantages and disadvantages; neither is perfect.

The question of custody

Unfortunately, however, in Nina’s case, the questionnaire worked against her, especially when, as she told me “the judge was not listening carefully during trial.” Not surprising, as the judges fall back on the filed documents to speak to them.

Nina’s lawyers might have disproved she was depressed but there remained the matter of child custody. That is, Nina’s depression, whether from unemployment or from post-partum, were both extraneous and would rectify when her situation changed. So, how do US courts decide child custody?

The difficult alternative Nina was givenMy advice to Nina to secure more time with her child was that she must take up the two-year offer her husband had made.

Her husband’s offer was that he would seek a separation and not divorce her for two years, so that she could continue to stay on her spouse visa in the US. His condition, however, was that she had to obtain a degree and a job in that time and secure her future in the USA. After this, he would divorce her, she would be on an H1B visa and they would share the custody of their child.

But Nina was skeptical this would work given the uncertainties that H1B workers suffer from and her own experience with unemployment in the USA.

I felt that Nina was too protected by her parents to be living alone in the US with no familial support. Not all women are made the same, and if the men in our lives cannot understand this, what other meaning is there to a marriage?

Divorce on H4 visa hard on dependent Indian womenIn a time when American women are finding divorcing during COVID-19 very hard, a woman on H4 visa is twice as likely to feel nervous.

Nina’s question was, “Why can’t he come to India where both parents can work and have equal custody? Why do I need to re-educate myself?” But because the child is an American citizen, the court system was likely biased towards protecting an American citizen.

“Why is everyone asking me to adjust although he is such a bad person?” Nina’s exasperation resonates with so many women. Obviously, Nina’s husband did not want to head back to India. Why would he? Not when everything was working well for him! Since Nina and her husband could not come to a consensus, the divorce case became contested and went into trial.

What worked against Nina was also likely the Hague convention that India has not signed. What this means is that if one parent abducts their child across international borders, the child can be returned, and the parent prosecuted. If only the husband had allowed for an OCI card!

Nina could have taken the advice of the Ministry of External Affairs Booklet’s advice to go for an uncontested divorce. But she was too angry and upset for that. When I asked her if she would be alright if the judgment rules her child to stay in the US, she just said that she knew something good was going to happen. She just felt it strongly and that she would take a chance with the judge. This despite her own lawyer’s frustrated declaration that if she won, “it would be a miracle!”

My own advice to Nina was to consider the cultural context. For instance, if the case had been filed in India, her Indian lawyers would have advised her to file a 498A to get justice. Similarly, Nina had to do something about child custody that was US culture sensitive. She had to offer a win-win solution, so the courts perceived her as prioritizing her child’s well-being. Child welfare is of paramount importance at US courts. But Nina was adamant, she left it to chance. That is a mistake in the USA, where everything is planned, reasoned out and anticipated well-in-advance. Nina had to think through the worst-case scenario and move forward. Instead, she was optimistic and hopeful.

Judgement ruled against NinaWhen the judgment ruled that the child stay with the father, Nina perceived it as harsh. Nina’s husband is ordered to buy her tickets for her 2-3 visits per year until the child turns six. At 12, the child can choose a parent. Being on an H4 visa, Nina must now return to India as soon as the divorce formalities are through.

The tragedy of this case is that what caused Nina’s depression in the first place, is also the cause for her loss of child custody and her divorce—the H4 visa. Clearly, nobody showed Nina’s husband this article published on Women’s Web. Husbands do not necessarily understand what unemployment in a cold, rainy city and caring for a child 24/7 can feel like—that of course, is patriarchy for you.

Dr. Sushumna Kannan owns Writing in Gold, a Writing-Editing service business based in San Diego, USA. She is the author of Hinduism and Violence, forthcoming, 2021. Check out her other writings at sushumnakannan.weebly.com

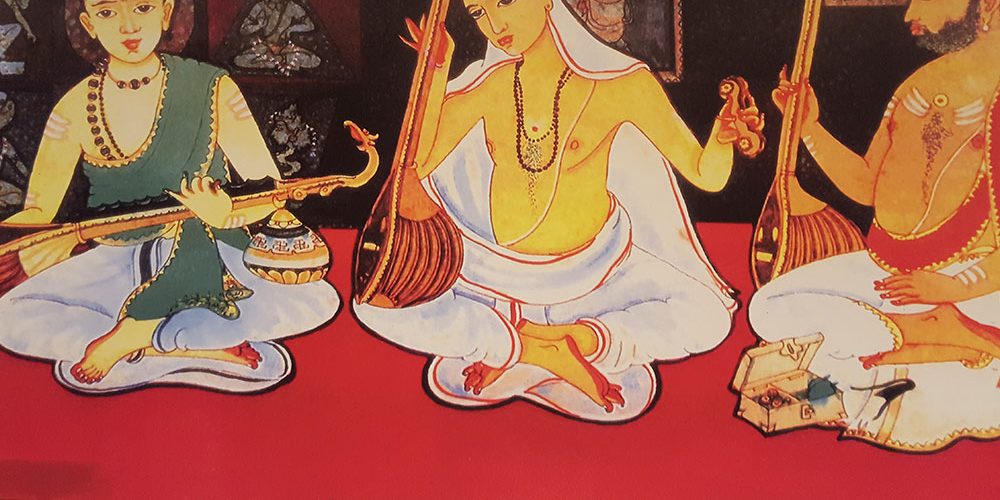

Naked Truth: Visual Representations of Akka Mahadevi

Sushumna Kannan

Akka Mahadevi, the 12th century saint from Karnataka, is a unique figure in India’s history. She walked away from her husband – naked – proclaiming continuously that Shiva was her husband. She rejected clothes, jewellery and the world itself. According to some hagiographies, hair grew from her mother’s tears and effectively covered her, but she walked away unaware. In other hagiographies, she was always naked. A digambare, clad only in sky. Or, a keshambare, clad only in hair.

But how to visually represent a worship-worthy woman who walked naked rejecting the world? This is a question negotiated by various stakeholders in multiple ways. Religious organisations, historians and feminists adopt various stances on the issues underlying Mahadevi’s nudity.

In calendar art, Mahadevi is represented in typical ways – meditating, worshipping the linga, or gazing neutrally. In one representation, her birth, her devotion, King Kaushika lusting after her, her rejection of worldly life and, finally, achieving oneness with Shiva, is shown. She stands on the globe in the map of India – a possible attempt to paint her as relevant. And in front of a bull, Shiva’s vehicle.

The Lingayats (Mahadevi’s religious community) shy away from visual representations of her nudity. Its discussion is embarrassing or must be resisted because it would only feed voyeurism, voiding the purpose of Mahadevi’s life. In 1998, Halage Arya, a 15th century saint’s version of Mahadevi’s life in the Shoonya Sampadane was refused publication by the associated religious organisation because it was explicit.

Historians too are divided on Mahadevi’s nudity. The meaning of keshambara is a matter of debate and it could be an object made of hair, or a shawl made of the furry coat of goats, argues H Deveerappa (1997). Kesha is assumed to be Mahadevi’s hair in the standard textbook story, but it could simply be any garment that signified renunciation, says Shanta Imprapura (2005). This is indeed how Mahadevi is represented in the temple at her birthplace, Udutadi. She is not clad in just any material signifying renunciation but in an ochre saree replete with a blouse, although it finds no historical substantiation. Mahadevi is decked with rudraksha and bhasma.

For Sumitrabai (1997), a feminist, why Mahadevi had to be naked and what pressured her into it is the crucial question. Even as she notes that nudity has a presence in Hindu traditions, she wonders if Mahadevi had agency in choosing nudity, concluding that nudity is a metaphor, symbolic of the spiritual life. Thus, while Lingayats may be weary of voyeurism, feminists refuse to grant the nakedness of Mahadevi as her own choice because they think she was forced into it. The tradition of nudity and womanhood merging seems like an unlikely event to these stakeholders occupying opposite ends of the spectrum

In the Shoonya Sampadane, when Mahadevi arrives at the city of Kalyana, Allama Prabhu questions her on her nudity because her long braids strategically cover her private parts. Did this not indicate shame and a continuing attachment to the world, he asks. Mahadevi replies that she covers her body so onlookers may not be embarrassed. When another saint, Kinnari Bomayya tests her out of a spirit of devotion, Mahadevi proves to him that she has reduced kama to ashes in the fire of her knowledge. Through a vachana, she conveys that donning light as garment she has subdued the darkness of the senses. Feminists read these incidents as harassment, whereas the spirit of empirical inquiry and dialogue is another viable reading.

That religious organisations, historians and feminists, all express embarrassment, denial or view Mahadevi’s nudity as symbolic suggests that current moral anxieties inspired by Victorian sexuality loom large. Perhaps, that is why, even now, Mahadevi must be always clothed in all her visual representations.

Arts Illustrated

An ascetic who never gave up her fight

The first female Lingayat monk, Mathe Mahadevi, raked up her share of controversies while continually challenging the status quo within her religious sect

In her youth, she was a one-woman brigade who took on powerful religious heads, her own family members and centuries of established practice. She went on to become the first female Lingayat monk and, eventually, ascended to the status of a jagadguru or world leader — a title traditionally reserved for an extraordinary spiritual leader.

Mathe Mahadevi, the Lingayat religious leader who passed away on March 14 aged 74, had stirred controversy in 2014 by calling on women to dress modestly and demanding the legalisation of sex work to reduce the incidence of rape. But she was active till the end in promoting the Lingayat way of life and demanding a separate religion status for Lingayats.

Born Ratna in Chitradurga district, Karnataka, to a Lingayat family of doctors belonging to the Ganiga or what was traditionally the oil worker’s caste, she wanted to pursue spirituality from a young age. At 19, she received initiation from her guru, Lingananda Swami, and entered monkhood a year later. The same year, claiming the spiritual legacy of the 12th-century mystic-poet Akka Mahadevi, after whom she was renamed, she brought out three collections of poetry — Mathru Vani (Mother’s Voice), Viraha Taranga (The Waves of Separation) and Ganga Taranga (The Waves of the Ganges). She later wrote several novels, including Heppitta Halu (Curdled Milk) and Tarangini (The River).

Her most path-breaking creation, however, remains the Jaganmata Akkmahadevi Anubhava Pitha, a spiritual post for women, which she set up in 1968.

***

Established by the 12th-century reformist-saint Basavanna, Lingayatism broke away from several entrenched beliefs in Hinduism. Many of the sutakas, or impurities, were abolished. For instance, Lingayat women can perform pooja during periods. Many sharanes (female followers of the medieval Veerashaivism sect pre-dating Lingayatism) were ascetic though married, and successfully straddled both worlds.

Yet, when Mahadevi decided to join her guru’s ashram in 1966, she faced stiff opposition. While Buddhism did create an order for women, Hinduism considered the rigours of ascetism not suitable for women. However, ascetic or even semi-ascetic women have always existed, whether as Brahmavadins of the Vedic period or the bhaktins of the medieval period. This was the larger context within which Mahadevi’s asceticism and life’s work took shape — there was a space for her and yet there wasn’t.

Holding a Master’s degree in philosophy from Karnatak University, Mahadevi was invited to complete a PhD at Cambridge University in 1976, after she delivered a nuanced lecture on Indian religions at a symposium in London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. She, however, chose a spartan life instead.

***

Mahadevi appeared to favour the West-endorsed, anachronistic and egalitarian interpretation of Basavanna’s vachanas or sayings, imputing to them a simplistic social activism rather than retaining the ambiguity of the philosophical-rhetorical questions raised by them.

In 1996, Mahadevi wrote the book Basava Vachana Deepti, wherein she declared a new birth date for Basavanna and changed the ankitanama, or signature, for his 1,342 vachanas to “lingadeva” in place of “kudalasangama deva.”

Predictably, this evoked large-scale protests from historians, littérateurs and religious leaders, leading to the government banning the book in 1998 for ostensibly hurting the sentiments of Veerashaivas.

The argument that the vachanas require commentaries by religious scholars to make them accessible to the contemporary reader is understandable, but the exegesis she offered created social and legal problems. Taking up her 2017 appeal against the ban, the Supreme Court initially said that it discouraged hypersensitivity in religious matters. Yet, in a U-turn of sorts, it dismissed her appeal later that year. Now, at Mahadevi’s passing, the time is ripe to re-evaluate her works from the perspectives of religion and secularism.

Mahadevi’s legacy of protest is numerous and varied. In 1996, she rallied against rituals through writings that urged people to stop prostrating at the feet of the jangamas (Lingayat teachers). In 2005, she published a book on what Lingayats ought to learn from the Sikhs. In 2007, she protested against the introduction of eggs in the midday meals at government schools in Karnataka, as also the proposal to declare the Bhagavad Gita as national text. For decades, she lamented that strict monotheism no longer prevailed in the Lingayat community, as followers began worshipping a large number of local gods. But monotheism is a Western construct and what Basavanna critiqued was the mechanical performance of rituals, forsaking genuine devotion.

In her early years, Mahadevi wrote that different traditions such as Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism were a part of Hinduism’s ‘solar system’. But in later life, she ended up demanding a separate religion status with minority benefits for the Lingayats, who make up almost 17 per cent of the population of Karnataka.

As early as the 1970s, she had conducted extensive fieldwork and research to elucidate the differences between the Veerashaivas and the Lingayats, and this was one of the factors that spurred the then chief minister Siddaramaiah to demand a separate religion status in 2018.

She cemented her status as a powerful female guru, first by setting up in Kudalasangama the Basava Dharma Peetha, an organisation dedicated to spreading the teachings of Lingayatism’s founder Basavanna, and later by organising the Saranamela, a worldwide conclave of Lingayats. She also lent her vision to the Rashtreeya Basava Dal, a Lingayat association with nationalist ideals.

More than anything, she was a living reminder of the complexity and diversity of religious traditions — an aspect that is often overlooked, whether by the pre- or post-Independence historian, or the school textbook writer, all of whom tend to homogenise them.

Sushumna Kannan is adjunct faculty at the San Diego State University

Published on May 03, 2019

The first female Lingayat monk, Mathe Mahadevi, raked up her share of controversies while continually challenging the status quo within her religious sect

In her youth, she was a one-woman brigade who took on powerful religious heads, her own family members and centuries of established practice. She went on to become the first female Lingayat monk and, eventually, ascended to the status of a jagadguru or world leader — a title traditionally reserved for an extraordinary spiritual leader.

Mathe Mahadevi, the Lingayat religious leader who passed away on March 14 aged 74, had stirred controversy in 2014 by calling on women to dress modestly and demanding the legalisation of sex work to reduce the incidence of rape. But she was active till the end in promoting the Lingayat way of life and demanding a separate religion status for Lingayats.

Born Ratna in Chitradurga district, Karnataka, to a Lingayat family of doctors belonging to the Ganiga or what was traditionally the oil worker’s caste, she wanted to pursue spirituality from a young age. At 19, she received initiation from her guru, Lingananda Swami, and entered monkhood a year later. The same year, claiming the spiritual legacy of the 12th-century mystic-poet Akka Mahadevi, after whom she was renamed, she brought out three collections of poetry — Mathru Vani (Mother’s Voice), Viraha Taranga (The Waves of Separation) and Ganga Taranga (The Waves of the Ganges). She later wrote several novels, including Heppitta Halu (Curdled Milk) and Tarangini (The River).

Her most path-breaking creation, however, remains the Jaganmata Akkmahadevi Anubhava Pitha, a spiritual post for women, which she set up in 1968.

***

Established by the 12th-century reformist-saint Basavanna, Lingayatism broke away from several entrenched beliefs in Hinduism. Many of the sutakas, or impurities, were abolished. For instance, Lingayat women can perform pooja during periods. Many sharanes (female followers of the medieval Veerashaivism sect pre-dating Lingayatism) were ascetic though married, and successfully straddled both worlds.

Yet, when Mahadevi decided to join her guru’s ashram in 1966, she faced stiff opposition. While Buddhism did create an order for women, Hinduism considered the rigours of ascetism not suitable for women. However, ascetic or even semi-ascetic women have always existed, whether as Brahmavadins of the Vedic period or the bhaktins of the medieval period. This was the larger context within which Mahadevi’s asceticism and life’s work took shape — there was a space for her and yet there wasn’t.

Holding a Master’s degree in philosophy from Karnatak University, Mahadevi was invited to complete a PhD at Cambridge University in 1976, after she delivered a nuanced lecture on Indian religions at a symposium in London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. She, however, chose a spartan life instead.

***

Mahadevi appeared to favour the West-endorsed, anachronistic and egalitarian interpretation of Basavanna’s vachanas or sayings, imputing to them a simplistic social activism rather than retaining the ambiguity of the philosophical-rhetorical questions raised by them.

In 1996, Mahadevi wrote the book Basava Vachana Deepti, wherein she declared a new birth date for Basavanna and changed the ankitanama, or signature, for his 1,342 vachanas to “lingadeva” in place of “kudalasangama deva.”

Predictably, this evoked large-scale protests from historians, littérateurs and religious leaders, leading to the government banning the book in 1998 for ostensibly hurting the sentiments of Veerashaivas.

The argument that the vachanas require commentaries by religious scholars to make them accessible to the contemporary reader is understandable, but the exegesis she offered created social and legal problems. Taking up her 2017 appeal against the ban, the Supreme Court initially said that it discouraged hypersensitivity in religious matters. Yet, in a U-turn of sorts, it dismissed her appeal later that year. Now, at Mahadevi’s passing, the time is ripe to re-evaluate her works from the perspectives of religion and secularism.

Mahadevi’s legacy of protest is numerous and varied. In 1996, she rallied against rituals through writings that urged people to stop prostrating at the feet of the jangamas (Lingayat teachers). In 2005, she published a book on what Lingayats ought to learn from the Sikhs. In 2007, she protested against the introduction of eggs in the midday meals at government schools in Karnataka, as also the proposal to declare the Bhagavad Gita as national text. For decades, she lamented that strict monotheism no longer prevailed in the Lingayat community, as followers began worshipping a large number of local gods. But monotheism is a Western construct and what Basavanna critiqued was the mechanical performance of rituals, forsaking genuine devotion.

In her early years, Mahadevi wrote that different traditions such as Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism were a part of Hinduism’s ‘solar system’. But in later life, she ended up demanding a separate religion status with minority benefits for the Lingayats, who make up almost 17 per cent of the population of Karnataka.

As early as the 1970s, she had conducted extensive fieldwork and research to elucidate the differences between the Veerashaivas and the Lingayats, and this was one of the factors that spurred the then chief minister Siddaramaiah to demand a separate religion status in 2018.

She cemented her status as a powerful female guru, first by setting up in Kudalasangama the Basava Dharma Peetha, an organisation dedicated to spreading the teachings of Lingayatism’s founder Basavanna, and later by organising the Saranamela, a worldwide conclave of Lingayats. She also lent her vision to the Rashtreeya Basava Dal, a Lingayat association with nationalist ideals.

More than anything, she was a living reminder of the complexity and diversity of religious traditions — an aspect that is often overlooked, whether by the pre- or post-Independence historian, or the school textbook writer, all of whom tend to homogenise them.

Sushumna Kannan is adjunct faculty at the San Diego State University

Published on May 03, 2019

Challenging decades of prejudices about body types and looks, Bengaluru-based The Big Fat Company puts plus-size actors centre stage

SUSHUMNA KANNAN

“Where does Shakespeare say Hamlet was lean or that Lady Macbeth was slim?” asks Anuradha HR poignantly. She is the founder of Bengaluru-based The Big Fat Company, a one-of-a-kind theatre group with an explicit agenda to cast only plus-size actors in its productions. The first of these, Head 2 Head, a retelling of Girish Karnad’sHayavadana, was recently staged at the Nepal International Theatre Festival, Kathmandu (February 25- March 4, 2019).

Hayavadana is well-suited for the theatre group’s objective of interrogating embodied identity. Its heroine Padmini is attracted to two men — Devadutta for his intellect and Kapila for his athletic body. When, in a strange turn of events, the two men decapitate themselves at a Kali temple, Padmini manages to reattach the heads with the goddess’s blessings, except she mistakenly switches the heads. The men come back to life and, over time, their bodies return to their original state, implying the dominance of the head. Head 2 Headdoes not agree with this ending, and instead questions the working of the mind-body complex.

Anuradha launched the company in 2017 after more than a decade of thinking things over: “The frustrated actor-me with no challenging roles to play came up with the idea in rebellion against stereotypical casting practices in theatre,” she says. The lead role, whether in a marquee production or a school skit, invariably goes to a presentable person, no matter how bad an actor they may be. The media too is complicit in promoting a certain kind of look — tall, slim, fair — while eclipsing all others.

A common lament about the cinema industry in India is that the cast, especially the lead actors, is often selected solely on the basis of looks. The country’s theatre industry is usually expected to project a more conscientious alternative, especially given that much of its early history in independent India was shaped by the leftist and socially-conscious Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). In reality, however, Anuradha and her fellow professionals at The Big Fat Company say theatre is equally rife with prejudices and stereotypes about looks.

Harking back to playwrights like Shakespeare, Anuradha points out that they rarely ventured beyond a one-sentence description of a character’s clothes or looks or props, before allowing the character to speak for itself. These minimal aids to the director never mention a body type or beauty as requirements. If our performative arts are leaning towards certain body types, then that is entirely the doing of deep-rooted cultural prejudice, reinforced by directors and viewers, she says.

The Big Fat Theatre Company of the UK, founded in 2018, echoes its Indian forerunner’s thinking. “Where in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet did he say that Juliet had to be a specific body type?” it says on its website. The plus-size actors reinterpret the classics, “to make real theatre with real-looking people”.

Asked what it would take for her company to keep doing what it does, Anuradha replies: “We do not want the company to be around forever; the whole point is to make it redundant.” She hopes plus-size actors will eventually find space in all plays, normalising their presence. After all, the role of the body in art forms is as “a site for defining individual identity, constructing sex and gender ideals, negotiating power, and experimenting with the nature of representation itself”, she says, adding, “and thus it holds the power to formulate resistance as well.” Her agenda is to offer deeper understanding of personhoods and communities beyond the body image, but using the body itself.

In Head 2 Head, this is achieved by eschewing traditional theatrical devices of narrative, character and dialogue. For example, Padmini interjects with a personal story — through movement — that is not derived from Hayavadana at all. The other personal stories in the play, too, are all about what it means to inhabit a plus-size body— the struggles with eating, relationships, sex, career, clothing choices and so on. Then there is a scene where the characters simply eat a Black Forest cake — one kilo of it — with zero dialogue to explain. The use of huge masks that almost cover the body and stand in for it, or alternately unveil it, is meant to draw attention to the corporeal form, inviting the audience to directly engage with the bodies on stage.

Head 2 Head was made possible by a combination of crowdfunding, financing from Untitled Arts and Anuradha’s own funds . Ahead of the play’s opening, there was a three-month workshop for 13 actors — who responded to an ad calling for plus-size actors — and another three months of production work with director Shabari Rao. The production has on board seasoned professionals such as Kriti Bettadh, Vidya Ulithaya, Sindhi Hegde and Goutham Upadhya. “Understanding and exploring the possibilities and limitations of our own bodies, both as individuals and performers, was the most exciting and challenging part,” says Anuradha.

After seven shows in Bengaluru, the group plans to take Head 2 Head in English to audiences outside Karnataka. Also on the cards is a one-woman show on sexual violence, which will go on stage next month.

Sushumna Kannan is adjunct faculty at San Diego State University

Published on April 04, 2019 in the Hindu Business Line, BLink.

Period. End Of Sentence: Worthy Message But No Riding On Shock-Value, Please!

At 25 minutes, Period. End of sentence achieves a lot. It moves us, provokes us and leaves us right when we wanted more. Yet, it suffers from its tendency to combine shock value with reformist overtones.

Made solely through the fundraising and other efforts of high school students in America, the short new docu-drama on Netflix explains many things, makes meaningful connections, offers hope – all without footnoting its title anywhere. There is no disagreement possible with the point of the film, its message is clear, and we love it too. Quite simply, we need to talk about periods, irrespective of whether we are in LA or in rural India. Yet, this Oscar nominated short suffers from one drawback common to many docudramas made in India and elsewhere.

It thrives on shock value and has reformist undertones. It is yet another agitating documentary with an omniscient interviewer. For instance, the film establishes that there is ignorance about periods by asking rural women, school children and teenaged boys about it. But it doesn’t realize that there is also some knowledge in the answers. To my mind, there is ignorance, but of the scientific findings of the last x years, not of the body basics. And the ignorance that is found is because scientific education has not reached Indian villages as quickly and efficiently as it should have. One lady in response to questions such as—what are periods, do you know why they occur and so on, says, that they occur due to impure blood exiting our body. This is not an entirely useless or unscientific description. The uterine lining shedding itself causes periods—that blood has no use and should not be retained. In this sense, it is impure, and the periods are cleansing. The idea that periods are a cleansing are mentioned in the dharmashastras. These texts also deem women to be very pure because such a cleansing bodily mechanism exists.

Then, when a bunch of teenage boys are asked about the period and they do not know, there is an embarrassing and shocking silence. The viewer feels it burn into her skin. And then comes the Hindi word. At which most of the boys say, oh we know. Hindi, anyone? A bit more sensitivity would have helped here. Treating your informants as also possessing some knowledge is generally a good idea.

Schoolgirls term periods as ‘women’s problem.’ A voice (film-maker/interviewer) asks, why problem? Again, describing periods as a problem is in itself not entirely wrong. Many women suffer their periods accompanied by cramps. So yes, it is a problem. Teenaged boys termed it an illness – which though wrong does not indicate the kind of supposed ignorance. It appears to be a description that took into account the lack of health or ease leading to dis-ease (bimaari) due to cramps. When activists try to change the narrative around a subject matter, they will do better if they build on the existing knowledge within communities rather than mock them.

Due to many such moments, it felt like the unfolding drama of the urban film-maker meeting the rural poor, a repeat of the coloniser meeting the heathen. And oh, outrage! In the viewer, in the film’s narrative, everywhere! A more open-ended inquiry, with questions and seeking would have been far more interesting. For instance, a question that bugged me was whether Indians always kept this topic under wraps or whether they learnt it from Victorian morality. Rural India might have some clues to this, but we must be willing to listen.

What is more puzzling is that from such outrage-narrative mode, the film moves onto a second phase – of whole-hearted celebration. It creates endearing characters and leaves us in awe of the wonderful entrepreneurship women are capable of – with a ‘whoever can stop women’ kind of moment. Suddenly, the film appears to be structured in two disjunct parts.

Leveling a sharp critique first, demanding change and then seeking to celebrate the women as they are, has its share of confusions, I suppose. Going by the excessive usage of such constructions found in the academia and elsewhere, it appears that this is no well-planned narrative technique adopted by the film, but a trajectory that has grown roots in feminist activism beforehand. I think we must challenge this to ask why we cannot celebrate women as they are – strong, pillars of families and societies – and then offer the additional help they need to make things even better. In other words, they are the agents to begin with, and were agents always! Instead, we meet them as ignorant and then they become empowered! This kind of happy-ending is a cliché in docu-dramas with a message and may well have been avoided.

Plus, where is the angle from an environmental perspective? Cloth, for containing period blood is inconvenient and insufficient, yes. But it was at least environment-friendly. There is no mention of whether the pads are reusable.

We would have to wait and see what happens to the film at the Oscars. Countdown jaari hai!

Published on Women's Web, Feb 13, 2019.

Niharika Singh’s #MeToo Story Makes Us Think Of The Precondition To Consenting

There is something called a precondition to consenting – Consent is not just about the ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ given but about the circumstances in which it is given. Niharika Singh’s story illustrates this best.

“This isn’t #metoo …. This is washing dirty linen in public for publicity. She wouldn’t be in a relationship for 1.5 years had he forced himself on her. Appalled at selective #metoo journalism,” says a woman in response to Actor Niharika Singh’s story, when she recently accused fellow actor and ex-boyfriend Nawazuddin Siddiqui of sexual harassment.

Since the #MeToo movement began, people have loved to play judges, weighing in and letting us know what is legitimate metoo and what is not. Of all the #Metoo stories thus far, Singh’s story captures the essence of this movement in full. No one said that Metoo is about sexual harassment at the workplace only. It is about sexual harassment in the various aspects of women’s lives. Consequently, women have documented and called out street harassment, as well as sexual assault within families and at the workplace.

Why cannot women be in a relationship and be sexually assaulted? If we are bracing ourselves to talk about marital rape, that is.

Singh writes, “When I opened the door, he grabbed me. I tried to push him away but he wouldn’t let go. After a little coercion, I finally gave in.” I am not sure how this does not qualify as sexual harassment. Especially since Siddiqui lied about a lot of things including relationships with other women. It is obvious that Singh did not want to be in a relationship with a man committed to others as well. Not knowing this at an early stage, when she hesitatingly gave in to his coercion, she has just behaved like a human being. A being who is open to a relationship with a hithertouncommitted man.

How should things have panned out for one to be able to describe what transpired as consensual?

The man in question would have befriended the lady he would have liked to develop a relationship with, put her first, found out what her expectations of a relationship are, proposed having a relationship and outlined why he thinks they should enter a relationship. After which, the lady would respond with a yes or no whenever she would feel comfortable doing so. This is consent.

Grabbing someone right at their door, not making a full disclosure about other relationships (past and present) and when the lady gave in, proceeding to take things to the next level is anything but consent. A gentleman and non-criminal person would have stepped back from a proposal for something like, sex with no strings attached, if the lady in question was drunk. So why make a proposal when the lady was in the dark and under a misconception about your status as a single person?

What has happened here is deep deception. This may not be a crime against the state yet, but it should become that, and it is definitely a crime against a woman and against humanity. So when you write: “Its no more crime vs innocence now..For women this has become men vs women Its really sad,” really? Is this not why ‘promise of marriage’ or ‘breach of promise’ and a sexual relationship is being debated in the Supreme Court of India?

As human beings with desires of their own, women enter into relationships all the time. There is no crime in that unless you are a petty moralist. They even tolerate lies and deception because they see men as fallible and choose to forgive. This does not mean they will always forgive. If they confront and call out their partners’ unacceptable ways and the partner does not respond humanely, the relationship ends. There is a sense of wasted time and effort at such a point of time. All the times the relationship stood solely on the ground of the forgiveness of the woman feels like what it actually was – betrayal and deception – the man abused her trust, used her and took advantage of her.

And may I remind readers that The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 is only five years old. Before this, women had no strong fora on which to make a complaint. So please stop asking: “What’s she doing till now. Eating pani Puri.” Or: “why didn’t you complain about it then”.

In a 2011 case, consent was understood as: “…voluntary participation not only after the exercise of intelligence based on the knowledge of the significance and moral quality of the act but after having fully exercised the choice between resistance and assent. Whether there was consent or not, is to be ascertained only on a careful study of all relevant circumstances.” Plus, according to section 90 of the Indian Penal Code, “…if a person is under… a misconception of fact,” consent cannot be given. In other words, there is a precondition to consent, and if this is unfulfilled, the consent given is suspect, or even invalid.

Niharika Singh talks about sexual harassment or unwanted sexual advances in a voice that all women who know what deception looks like will instantly identify as true and credible. Siddiqui’s carefully constructed narrative in his memoir, of a naïve man wondrously and comically detached from the events in his own life can only fool a few.

Images via IMDB

-Sushumna Kannan

Published on Women's Web, NOVEMBER 21, 2018

THE VISUAL NARRATIVE OF JANAPADA LOKA, A MUSEUM OF FOLK ART

November 01, 2018

By Sushumna Kannan

Janapada Loka, literally ‘folk world,’ is a museum of folk art and culture spread across 15 acres along the Bengaluru-Mysuru Highway near Chennapattana, in Ramanagaram district, put together single-handedly by the well-known civil servant, late H.L. Nage Gowda. The museum offers a peek into quickly-vanishing rural lifestyles through objects of utility as well as ornamentation.

The huge metal entrance gate has an embossed sun and four bugles, underlined by a row of small terracotta peacocks, with brick and metal pillars on either side. One uses the small gate to enter the premises. Janapada Loka is dotted by a few buildings, each at a short distance from the others. The three museum buildings are: Loka Maatha Mandira, Chitra Kuteera and Loka Mahal. In addition, there is an open-air theatre, a college for folk arts built with bricks and clay tiles for roof called Doddamane, a water tank and a cafeteria called Loka Ruchi that serves North-Karnataka cuisine and is run by Kamat Yathrinivas.

The Loka Maatha Mandir consists of a collection of various objects from all over Karnataka. Framed copies of paintings that were once inside homes in Shimoga, Tanjore style painting of the deity Srinivasa, which is a traditional wedding gift from mothers to daughters over generations, pictures made of bead work, containers of various kinds used in farms and villages, cattle bells, tools, baskets, pots used in village households, big wooden trunks, wooden cribs, writing desks, containers used to store paddy, mirror frames, vegetable cutters and a traditional dustpan are all part of this collection.

The Chithra Kuteera consists of photographs of folk artists and varieties of Yakshagana make-up, a dance form specific to parts of Karnataka. The interior of this smallish circular building consists a collection of H L Nage Gowda’s manuscripts, published books, video footage, awards and photographs. The Loka Mahal holds life-size plaster of Paris moulds of a decorated bull, of characters from various styles of Yakshagana which are based on puranic stories. A life-size Kodava couple, a life-size dasayya or wandering mendicant, tools, bead ornaments used during a marriage in Belgaum, colour-painted terracotta ‘idols’ of Gods and Goddesses arranged in nine steps as during the Navaratri festival, among which are a Mary and Christ. Reproductions of ‘daivas’, Yakshis, ‘vigrahas’ and reproductions of imaginary or mythical birds and animals are also displayed here. Wooden kitchenware, from a rolling pin to measures of various sizes, clay lamps and a rare jangama nail-encrusted wooden sandal are all in glass encased showcases. Life-size wood sculptures of Yakshis and bhootas and sculptures of Ganesha, Raavana and Nandi are arranged within a structure of pentagon-shaped walls. The first floor of this building consists of leather shadow puppet characters of different styles, many centuries old. String puppets of characters commonly narrated along with the many decorated moulds of masks, a queen and a devi are also displayed. Musical instruments, games, and manuscripts are found here. The outdoor museum comprises mainly of sculptures and two chariots.

The visual narrative that Janapada Loka presents is quite clearly akin to that of museums that offer a nation-building narrative. Here, nationhood is synonymous with modernity and there is nostalgia and longing for the vanishing past, as it were, which is rural life. One of the burdens of nationhood is narrativizing tradition or writing history, since tradition must be preserved, celebrated and justified. While Janapada Loka participates in this narrative, through its own historical ‘implicatedness’ and its engagement with the museological discourse, it also evokes reflections on the notions of culture and ‘folk culture.’ Janapada Loka presents a somewhat open-ended narrative of its objects; though deeply invested in the traditions of Karnataka.

The rhetoric of presentation of museums, has, over time, had to change from one of a conversation among connoisseurs to one where scholars imparted knowledge to the unlettered and this motto is what the ideal citizen-subject invests in—as did the late H L Nage Gowda. This lofty aim is reflected in his foreword to A Catalogue: Janapada Loka: “…it is time for one and all to realise their [museum’s] potentials as sources of unlimited knowledge, experiments, research and as MEDIUM OF FIRST HAND EDUCATION.” [sic] And although, museums in the west have long marginalized the collector’s subjectivity to that of a curator’s struggle, one can find Janapada Loka constantly swaying between the two, for, Gowda’s personality and single-handed achievement looms large over Janapada Loka, which is largely a citizen initiative.

The privileging of vision and the selection of objects makes the museum a rationalizer of the natural world, whose diversity and differences are unmanageable in the singular story of the progress of mankind that museums often tend to tell. The question that still remains for us is, of course: how might we understand a collection of objects that are arranged and displayed for hundreds of people to see, which was not the purpose for which these objects were created? However, in postcolonial museums, it appears, it is not art that is preserved, but history. It is not as if the aesthetic object must be emptied of its meaning within the museum walls, but that straightaway what is preserved is preserved for its value in history. Thus, unlike western museums, there is no standard narrative of evolution that Janapada Loka presents in terms of a time frame or skills gained or materials used, although the narrative invests in progress through education and the urgent need to convey the richness of a culture and tradition. Equally interestingly, Janapada Loka combines industrial arts and decorative arts through its display of farming and cooking tools and paintings and representation of art forms, which were distinguished in the early history of the museum in the west.